Source:

Enhancing radiation-induced reactive oxygen species generation through mitochondrial transplantation in human glioblastoma

Scientific Reports | (2025) 15:7618

http://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40038364

Excerpt from abstract:

“Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most aggressive primary brain malignancy in adults, with high recurrence rates and resistance to standard therapies. This study explores mitochondrial transplantation as a novel method to enhance the radiobiological effect (RBE) of ionizing radiation (IR) by increasing mitochondrial density in GBM cells, potentially boosting reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and promoting radiation-induced cell death. Using cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs), mitochondria were transplanted into GBM cell lines U3035 and U3046. Transplanted mitochondria were successfully incorporated into recipient cells, increasing mitochondrial density significantly. Mitochondrial chimeric cells demonstrated enhanced ROS generation post-irradiation, as evidenced by increased electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signal intensity and fluorescent ROS assays. The transplanted mitochondria retained functionality and viability for up to 14 days, with mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequencing confirming high transfection and retention rates. Notably, mitochondrial transplantation was feasible…”

(Emphasis added.)

Interpretation, any errors my own:

- Human brain tumor-derived cells in culture were selected for use in a study examining a hypothesis that increasing mitochondria numbers in the cancer cells would result in greater vulnerability to cell death after exposure to radiation. If the hypothesis was supported, this could point toward a way to improve the radiation therapy tumor response in human brain cancers.

- The cancer-killing mechanism proposed for examination was simply that increasing the number of radiation-damaged mitochondria within cancer cells would hasten their death after the therapy. Such damaged mitochondria would function poorly and so produce greater amounts of toxic products, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS).

- The method chosen to increase mitochondrial numbers in the tumor cells was isolation of native mitochondria from cell lines of the same or an alternate similar type; after tagging these with stains for visibility, and with peptides known to promote entry into cells, the fresh mitochondria were added to the cancer cells in culture. Mitochondrial entry into the tumor cells was expected, as has been shown in many studies of mitochondria transfer.

- The outcome examined for was a significant increase in the ROS production in mitochondria-treated cells, compared with control, untreated cultures.The study outcome measures supported the hypothesis; the experimental cells that had their mitochondrial numbers increased by the transfer, and did produce significantly higher amounts of ROS. This suggests continued exploration of the transfer technique, as clinical use may be possible after further study.

Thought-provoking additional findings:

The mitochondria that were transferred into cells, either from the same line or an alternative line, showed persistence and function in their new cells. They “took root”.

Because mitochondria are mobile within and between cells, some degree of merging, called fusion, between native and newly entered mitochondria was expected. Fusion makes possible the exchange of genetic material among different individual mitochondria, aided by their resident partial genomes being bacteria-like, small, circular, lacking a protective membrane, and present in multiple copies. This fusion and genomic mixing was demonstrated, by sequencing of the mitochondrial genomes in the treated cells and finding sequences from both types of cell lines present in frequent combination with one another.

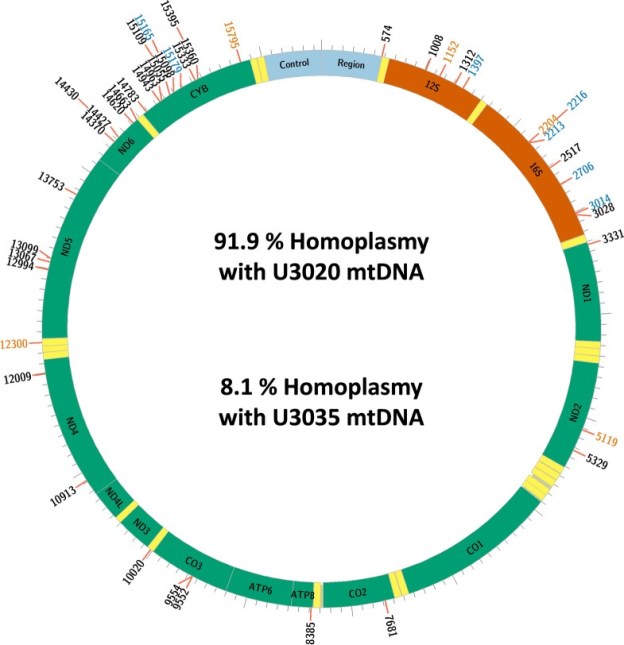

In those cells that had received mitochondria from an alternate line (“chimeric” cells, bearing two lineages of mitochondrial genomes) the sequencing made it possible to distinguish between genomic sequences that were original, and those sequences that had originated from the transferred alternate line of mitochondria. Fusions of new and original genetic elements, a virus-like process called transfection, were indeed found. In fact, the newly entered mitochondrial genome sequences were shown to nearly completely replace the originals in the chimeric cells. The group has illustrated this finding in the colorful chart below.

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/core/lw/2.0/html/tileshop_pmc/tileshop_pmc_inline.html

Here in the chart, “homoplasmy” means “these DNA sequences fairly uniformly match up with reference sequences”. (And heteroplasmy is when sequences do not match up in this way.) U3020 is the mitochondrial donor cell line, U3035 is the recipient. And the long designation U3035Mt20-X3 refers to those recipient cells, treated with a higher dose of the U3020 mitochondria.

“…it was found that the DNA sequence in the 14-day post-transplant U3035Mt20-X3 chimeras was most similar to the donor U3020 line and had only retained a small proportion of the recipient mtDNA sequence.”

The donor DNA sequences had substantially replaced those of the recipient’s original genome. Perhaps general similarity of these human cancer-derived cell lines helped here.

Within this group’s model, this last finding is a demonstration of a process I have long wished to know more about. I can’t say how applicable the result is beyond this model, or how generalizable these findings are.

Why do I see potential in this finding? Think about the discussions we are beginning to hear concerning replacement of human mitochondria as a therapeutic method comtemplated for many conditions. This idea assumes that the native mitochondria in any of us exist with varying degrees of damage accumulated in the process of their constant biochemical activity. This damage does specifically include mitochondrial DNA deletions, missing or mistaken base pairs, resulting in errors in the ribosomes or proteins produced, and so leading to impairment of function. Long exposure to the active biochemistry of the mitochondrion leads to these, causing a loss of information that is necessary not only for transcribing mitochondrial proteins, but also the production of new mitochondria, or mitochondrial “biogenesis”.

This biogenesis is a cooperative readout of mitochondrial genes that have become located over time in the protected, membrane-enclosed cell nucleus, along with genes present in the smaller and more fragile remnant mitochondrial genome. Gene sequences from both these locations are necessary, and the small mitochondrial genome that remains does encode critical genes for energy production and other essential functions. Together these gene transcripts make possible assembly of new replacement mitochondria. But as DNA deletions will accumulate with time in the mitochondrial genomes in a nearly universal process, the mitochondria resulting from biogenesis will unavoidably have corresponding impairments and loss of efficiency. Credible theories of aging have been built around these observations.

The goal of restoring competent mitochondria in an ill patient, or in any of us as we age and suffer impairments, may be reached at some near-future point, given progress in techniques of harvesting mitochondria from various types of cells in culture. Mitochondria newly harvested from cell cultures should initially show a minimum of damage and deletions.

Metaphors used to make this proposed restoration process understandable have often originated from the well-known “powerhouse of the cell” image, a largely true but very incomplete description. And so these ideas are communicated in terms of reconnecting power sources or replacing batteries. There may be a certain aspect of true representation here; research findings have often shown that transferred mitochondria may arrive in recipient cells competent and able to function energetically.

But the mitochondria also store genomic information necessary for their function and continued biogenesis. When through illness or aging, mitochondrial DNA deletions have accumulated, will transferred more complete mitochondria be able to make up for these losses? Are new mitochondria imported into cells able to effectively lend their more intact genomic information into the recipient mitochondrial network through fusion, with subsequent replication of the mingled DNA favoring restoration of the information missing through deletions present in the recipient cell? If that were a possible outcome, biogenesis could again produce complete and competent mitochondria in ongoing fashion.

We can’t yet know for certain about a hoped-for therapeutic genomic restoration from this one study in cultured human cancer cells; but these findings do show a near-complete replacement of the recipient mitochondrial genome by sequences from the donor cells. A demonstration of what may be possible for therapeutic use in disorders of mitochondrial function, including many chronic diseases and pathologies of aging.

Another thought-provoking finding in the mitochondrial transfer field; there have been very many in recent years. I feel that increased interest and investment in this area will lead to advances in clinical medicine, in the near future.

You just can’t get more proximal to the biochemical action of our kind of life, than mitochondria.